Like many of

you, I have been devastated by the outcome of your elections. I am trying to

make sense of what seems to me to be a giant step backwards for human rights, a

blow to tolerance and respect. The whole world seems to be swinging back into a

racist and colonialist mentality. First Brexit and now this. Major European

countries have upcoming elections soon and I fear that those will follow this

same right-wing trend. I can’t imagine what it must be like to be Obama and

look back on 8 years of his life and wonder what the hell he achieved. There is

no sense to be made.

I try to hide my

head in the sand – why should I care about American politics when Americans

seem to care only about themselves? But the reality is that when America

sneezes, we catch cold. I’ve always tried to console myself with the idea that

the American government is not necessarily the American people; that whatever

wrongs the government commits it doesn’t mean the ordinary people are racist or

islamophobes or … but now it seems that the people have spoken.

How is it

possible that someone who openly supports racism and sexism and blatantly spouts

hate-speech can have the support of more than 50 million people? Have we learnt

nothing from history? Even if, as they say, most Americans are insular and ignorant

about global events, have they learned nothing from their history? Nothing of

civil rights and segregation and hatred and war and violence from your past?

Yesterday my

daughter showed me that a proposed “victory” march by the Ku Klux Klan was

trending on Facebook. I read in the Sunday newspaper that your

president-elect’s father had been arrested at a rally years ago. He had been

wearing the gown of the KKK. It sent shivers down my spine.

My son is in the

USA and, like many of his friends, couldn’t wait to get out of his school

uniform and grow his hair and beard. And from 12000 kms away, here I am

freaking out about him looking like a “terrorist”. He is adamant that he is not

going to shave and it goes against everything that I believe in to try and

convince him that he should toe the line, lie low and not look a certain way. He

probably wonders what I am on about since, even without the beard, he gets

stopped at every airport for “random” security checks because of the way he

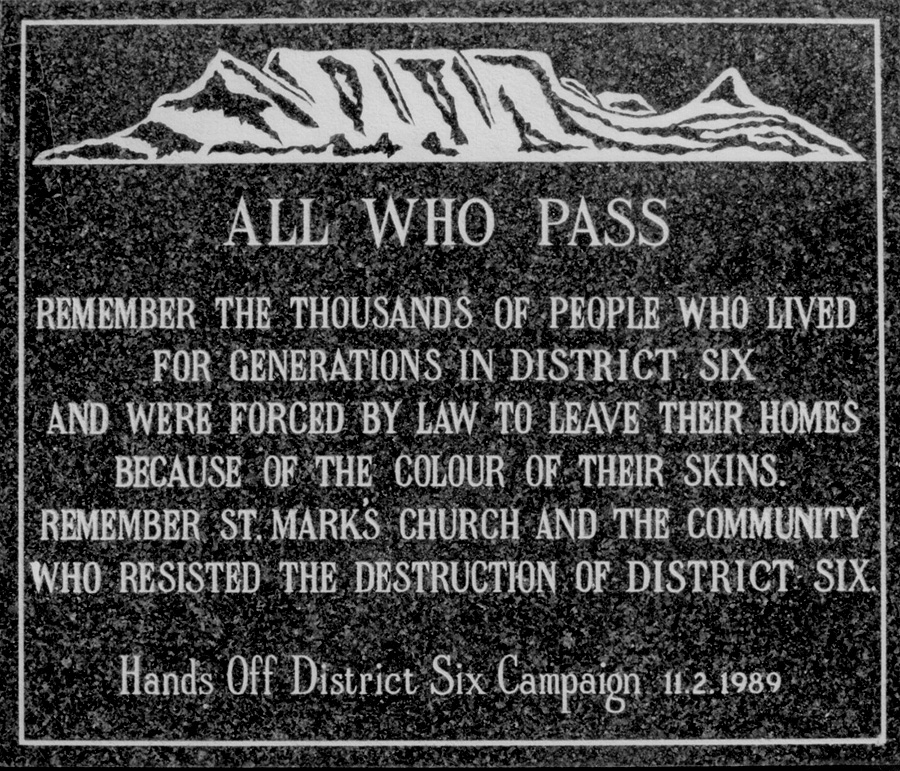

looks. This feels like apartheid happening all over again.

There have been

many articles written by experts in the fields, opinion pieces by academics and

political commentators, pleas for tolerance and against panic. I’m trying to

find comfort in the calls by diverse people for sanity to prevail, for people

to take time to reflect and heal, and then to take action by forming community

support groups, of becoming involved with NGO’s, of reaching out to their

neighbours, to Muslims, Hispanics, Jews. Perhaps that’s all that we can do. To

build small circles of compassion and to create ripples until, hopefully, we

have concentric circles of goodness to protect and strengthen ourselves.

I was reminded

this morning of a quote by Pastor Niemoller, a German who spoke out against the

Nazis and was detained at Dachau. This is what he said,

First they came

for the socialists and I did not speak out because I was not a socialist;

then they came

for the trade unionists and I did not speak out because I was not a trade

unionist;

then they came

for the Jews and I did not speak out because I was not a Jew;

then they came

for me and there was no one left to speak out for me.

In the dark days

of apartheid that quote was pinned to my notice board. I found comfort in it

then. I hope that it can still comfort now. And when I have energy perhaps I

will heed Toni Morrison’s words:

There is no time

for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We

speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilisations heal.

I hope that she’s

right. In the meantime, please take care

of my son – underneath his tanned skin and beard is a good, kind man.