|

| Family and Friends Woodstock/District Six circa 1940s My grandmother holding my mother on the right |

|

| My father in his rugby-playing days circa 1950 |

My life revolved around Hanover Street, the main artery which ran all the way up from the city centre, into Walmer Estate where I grew up. My grandfather’s tailor shop, later to be taken over by my uncle, was a hive of activity there; the doctor who delivered me in my grandparents’ home, had his surgery there where we would queue for hours to be seen, and Majiet’s barbershop was filled with people not necessarily having their hair cut, but playing dominoes and catching up on the news. A trip into town would inevitably involve a stop for roti and curry from the Crescent Café. My father says that you could buy anything in Hanover Street except petrol.

Central to the area was the spirit of kanala – a Malay word for “if you please”. Before it became District Six , the area was called Kanaladorp, a mixture of Malay and Dutch, referring to the way people assisted each other, or did favours for each other – a version of Ubuntu.

|

| Malay choir photo courtesy Ismail Lagardien |

Tied up with my memories is the music which was played in the streets by minstrels, Malay choirs and Christmas bands, and the food with names like bredie, bobotie, denningvleis, frikkadels and oumens onder die kombers. One dish that, for me, represents the Cape with Malay, Dutch and Christian influences blended together with fragrant spices was pickled fish. I remember my maternal grandmother making it in the last week of Lent, to eat on Good Friday. She would make it well in advance to give the spices a chance to penetrate the fish, and also to free up her Friday when she would spend many hours in church. The best fish to use was geelbek, kabeljou or yellow tail which would have been bought either from the fish market on the corner of Hanover and Clifton Street, opposite the Star bioscope, or from the fish cart which did the rounds in the neighbourhood. The hawker would sound his horn to alert housewives that he had arrived with the catch of the day and they would come out to the street to haggle.

|

| Weddings were communal affairs |

Weddings and funerals were community affairs. When I was about six or seven I was a flower girl twice in the same year, once for my aunt, a Christian wedding and then for a Muslim neighbour, a dressmaker who sewed all the dresses for the wedding herself. The whole street turned out to see the bride when the wedding cars hooted to announce her arrival, and the neighbours followed behind to the reception in the Princess Street Hall. Funerals were another occasion when everyone would just turn up to pay their respects and support the family in any way they could. Christian men would borrow fezzes and take their turns carrying the bier of their Muslim neighbours.

As the bulldozers moved in and the walls came tumbling around her, my paternal grandmother was banished to Mitchells Plain, far from the city centre where she had lived her whole life. She had been a fiercely independent woman, who had to earn a living after her husband died and left her to raise four children on her own. She made koeksisters and konfyt to sell door-to-door on Sunday mornings in District Six, and sewed and crocheted. She used public transport or walked wherever she had to go. What I remember most was her loss of independence. Suddenly she found herself in a foreign area without any infrastructure and no public transport to fetch her pension from the General Post Office in Cape Town. For the first time she had to ask for help.

|

| My grandaunt and friend snapped by street photographer while walking past the GPO |

|

| Wall in District 6 Museum bearing names of former residents |

|

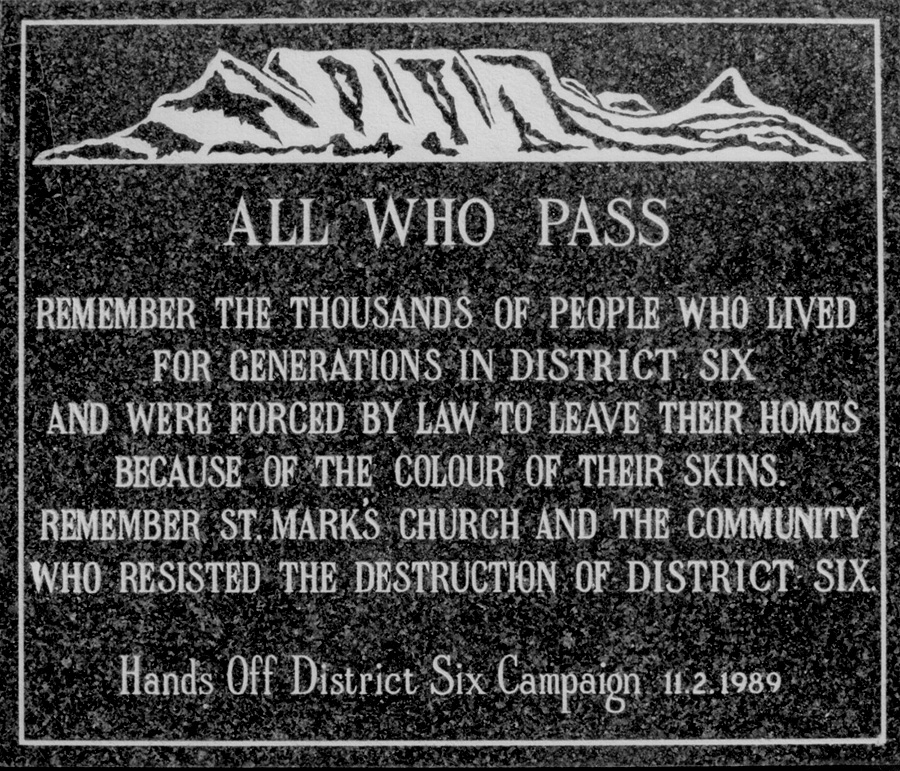

Memorial Plaque at the District Six Museum

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1d/District-Six-Memory-Plaque.jpg

|