I have been immersed in Isabel Wilkerson's book, an account of the decades-long migration of black citizens who fled the South for the northern and western cities, in search of a better life between 1910 and 1970. This epic story covers an exodus of six million people but Wilkerson follows the journey of three main characters, each representing a different decade of the Great Migration: Ida Mae Gladney (1930s), a share-cropper's wife who left Mississippi for Chicago, George Starling (1940s), the valedictorian of his "coloured" high school class in Florida who escaped lynching in Florida and landed up in New York and Robert Foster (1950s), a Morehouse-educated surgeon from Louisiana who finds himself in California.

Wilkerson writes easily about difficult subjects - I was shocked at the brutality of the conditions they were escaping and I had no idea of the extent of what she calls the Great Migration, before I went to the MoMA on our recent visit to the USA.

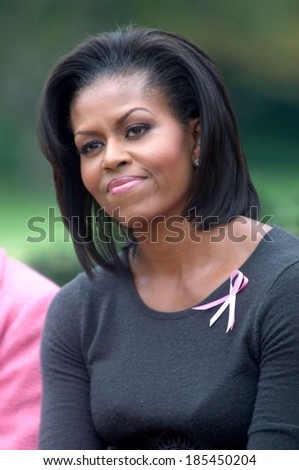

Wilkerson's mother left rural Georgia and her father southern Virginia to settle in Washington, D.C., so she has a personal interest in this story. She has done a great job of bringing the stories to life and recording it for generations to come. In her Epilogue she mentions some of the many well-known children of people who left the South to give their children the opportunity to grow up free. These include Toni Morrison, Michelle Obama, Serena and Venus Williams, Michael Jackson, Diana Ross and Oprah Winfrey.

|

| Michelle Obama |

| Oprah Winfrey |

I was deeply moved by this work of narrative non-fiction which humanises a history of race, class and politics. It is the author's revelation of the personal details of the struggles of ordinary men and women which brings this story alive.

For more on the Migration in this blog, see Jacob Lawrence and the Migration Series

Images of Obama and Winfrey courtesy of www.shutterstock.com

Image of book cover from: http://isabelwilkerson.com/