|

| Kimdendhri Pillay-Constant (facilitator) with authors Veronica Kroukamp and Naema Moses |

Aunty Veronica is one of the many women living behind the headlines of:

Aunty Veronica remembers crying when she moved into Constitution Court No. 48 in 1981, because she had “always heard and seen what happens in this place”. Her children were afraid to play outside, they witnessed a gang killing, when she came home from work at night, neighbours would have eaten the food she had left out for her children. Through it all she was determined to make sure that her children would not be brought up “like the neighbours”. She speaks proudly about her children overcoming challenges to find a way to earn a living.

In spite of this, her story is punctuated with headings like, Facing Danger and Change in the Community, The Life and Death of My Son, Tough Times with My Daughter Sonia, and My Daughter Roundel Who We Almost Lost a Few Times. The story is a rollercoaster of suicide attempts, battles with drugs, abuse and violence but a determination to overcome shines through and she ends her story with the words:

I will come out on top. I will achieve the things I want in life even if I must do the subjects over, I will do it because I still believe that I will get my grade 12 certificate before I am going to be 60 years old.

Aunty Veronica was one of the speakers at a meeting of the Non-Violence Vocal I attended recently. She is one of the authors of a book, Women Surviving Lavender Hill, which emerged from a two-year writing project facilitated by New World Foundation. The project was started a healing process for women to address the trauma and abuse they have endured through living in a community such as Lavender Hill, a community of gang violence, drug and alcohol addiction and domestic violence.

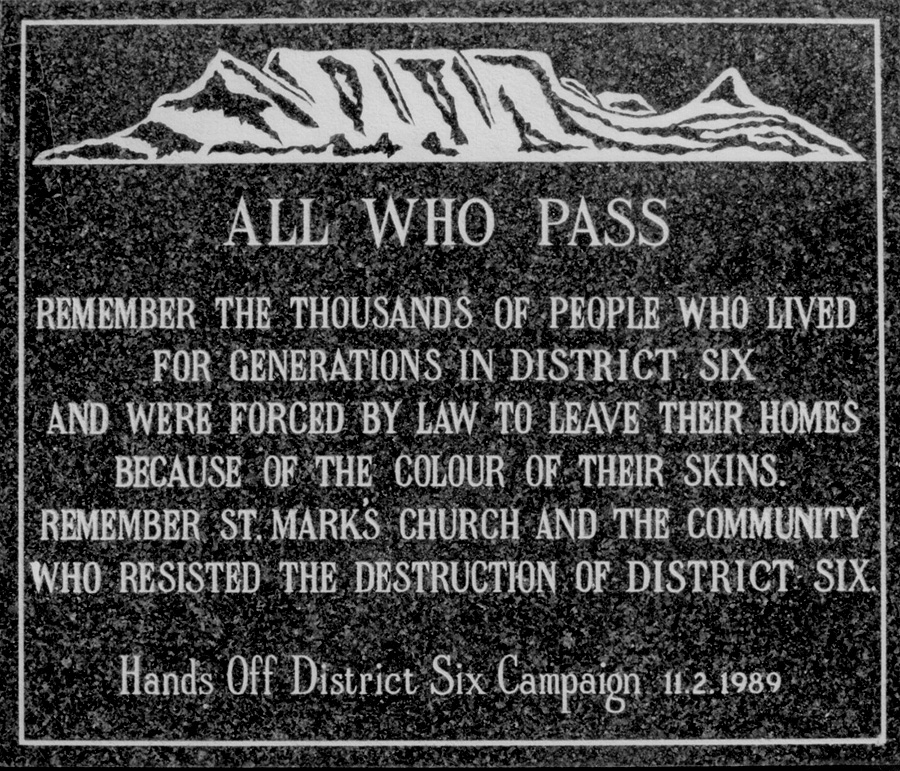

Places like Lavender Hill are the scars we bear from the apartheid legacy of forced removals when culturally diverse communities from District Six in the city centre to Claremont, Harfield and Bishopscourt, in the southern suburbs, to Simon’s town along the False Bay coast, were disrupted and the lives of ordinary people destroyed in the classificatory madness of the National Party.

These depressing headlines immediately pop up on a cursory search on the internet, but I feel that I owe it to Aunty Veronica to share some of the good news stories that defy any ideas that we may have of the real people who live in communities like Lavender Hill. Like the Waves for Change surfing project, the Lavender in Lavender Hill job creation project, and the story of Lavender Hill resident, Riaan Cedras ,who went from cutting grass to graduating with a PhD in Marine Science this year.

The book is self-published and reflects the stories of the women in their authentic voices, is available from New World Foundation: admin@newworldfoundation.org.za.