|

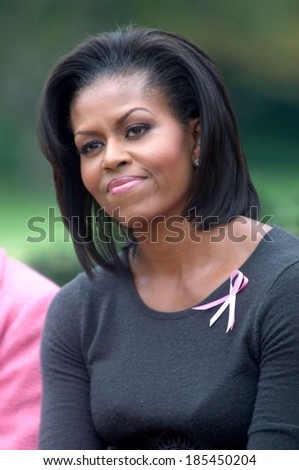

| Photo taken at District Six Museum 2015 |

I am reading William Pick’s The Slave has Overcome, and the humiliation of being a student in the medical faculty of the University of Cape Town during the 1980s, has coming sweeping back in waves over me. Professor Pick is the former head of the School of Public Health at Wits University and President of the Medical Research Council and holds a string of other awards and accolades including a fellowship from Harvard University. He tells his story as a descendant of the historically-repressed indigenous Khoisan people who overcame the barriers of apartheid to become an internationally recognised leader in the field of Public Health.

Prof Pick studied medicine at UCT in the 1960s. It was painful to read of the discrimination he faced and to be reminded of the same issues which I experienced 20 years later – the difficulties of travelling from the Cape Flats to campus, the awkwardness of being able to sit next to whites in lecture theatres when we couldn’t sit next to them in restaurants, not being able to treat white patients, not being able to dissect a white cadaver…

In the hospital you were able to work out the race and sex of your patient without even seeing them – the folders were green for blacks and pink for whites, a number in the corner of the name labels classified patients according to race and sex with number 1 being equal to "white male", 2 for "white female", 3 for "coloured male" and so on until the classification at the bottom of the hierarchy was "black female".

I remember having great difficulty as a third year student on my first psychiatry placement at Valkenberg Hospital in the coloured ward where a mix of neurotic and psychotic patients had been dumped together because of a lack of facilities. My supervisor sympathised with me but said her hands were tied because I couldn’t be placed in the white ward at Groote Schuur Hospital.

In the last while I have been disturbed to hear opinions that this government is worse than the apartheid government. I, too, am angry at the slow rate of transformation, but sympathetic at the overwhelming burden of the apartheid legacy of gutter education, inferior health care and segregation at every level and I am insulted when I am told that apartheid wasn’t that bad, that it’s over now and we must move on.

To say that apartheid was better than what we have today is to dismiss the suffering and humiliation of millions of people, the death and torture of thousands more and the brainwashing of generations of people who believed that they were inferior or superior and had a right to treat fellow human beings in a certain way because of the colour of their skins. To say that apartheid was better than what we have now is to minimise the suffering of all those forcibly removed from their homes, those denied entry to university. To say that apartheid was better than what we have today is to give the perpetrators permission to pat themselves on the back and smile smugly because they were justified in treating black people the way they did.

I salute Prof Pick and the countless others who, like him, have overcome the legacy of apartheid to excel in spite of the barriers.